Date: April 8, 2020 (Lecture Video, iPad Notes, Concept Check, Class Responses, Solutions)

Lecture 18 Summary

- Intro: Another Example of Bayesian Networks

- Setting it Up

- Specific Example of Inference

- Back to Original Setup: Choosing the Order of Elimination

- What does the min cost of inference depend on?

- How to get Optimal Order for Polytrees

- Preview to Next Lecture: Hidden Markov Models

- Final Notes

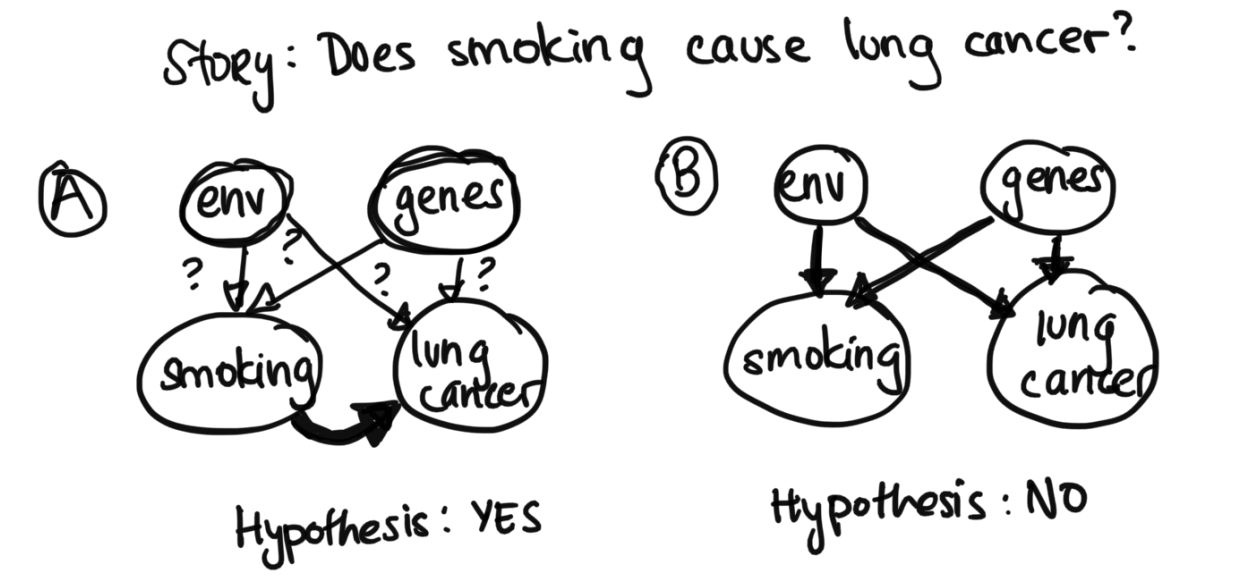

Intro: Another Example of Bayesian Networks

Last time, we defined Bayesian Networks, and we saw how they are useful in the probabilistic setting regardless of whether we're in the unsupervised or superivsed world, as it helps us describe structure in the data Today, we will cover how to do inference in Bayesian netowrks.Before moving on, we'll look at a real world application of Bayes Nets. While nowadays most people know that smoking is damaging to the lungs, in the past, this was an open question. Because we couldn't do a randomized trial where we made one group smoke and another group not (due to ethical concerns), we were never able to tell the difference between correlation and causation. Even though it looked like the rate of lung cancer is higher in smokers than nonsmokers, tobacco companies and other argued that perhaps the same genes lead to people getting lung cancer and wanting to smoke. Or, perhaps growing up in a certain enviroment causes both the lung caner and an increased likelihood to smoke. Does smoking actually cause lung cancer? It was impossible to tell (see diagram below, for the two hypotheses in Bayes Nets Form).

Setting it Up

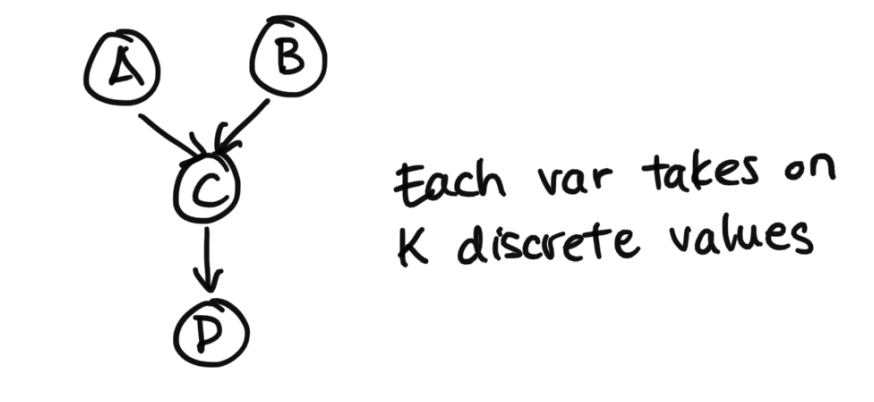

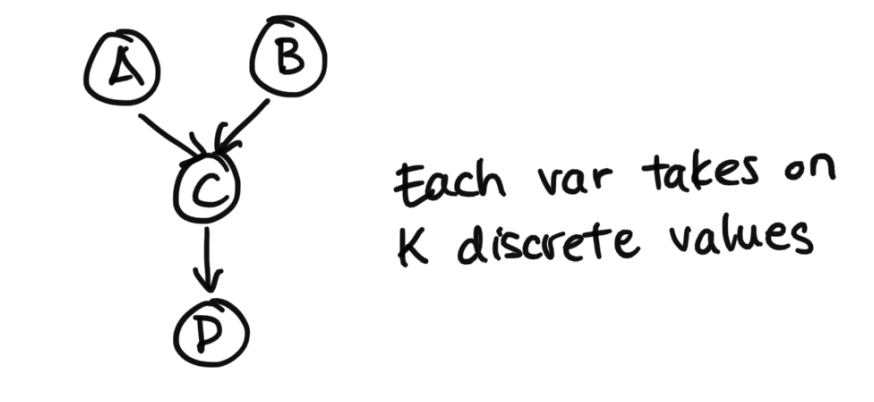

Let's say we have this following setup.

Specific Example of Inference

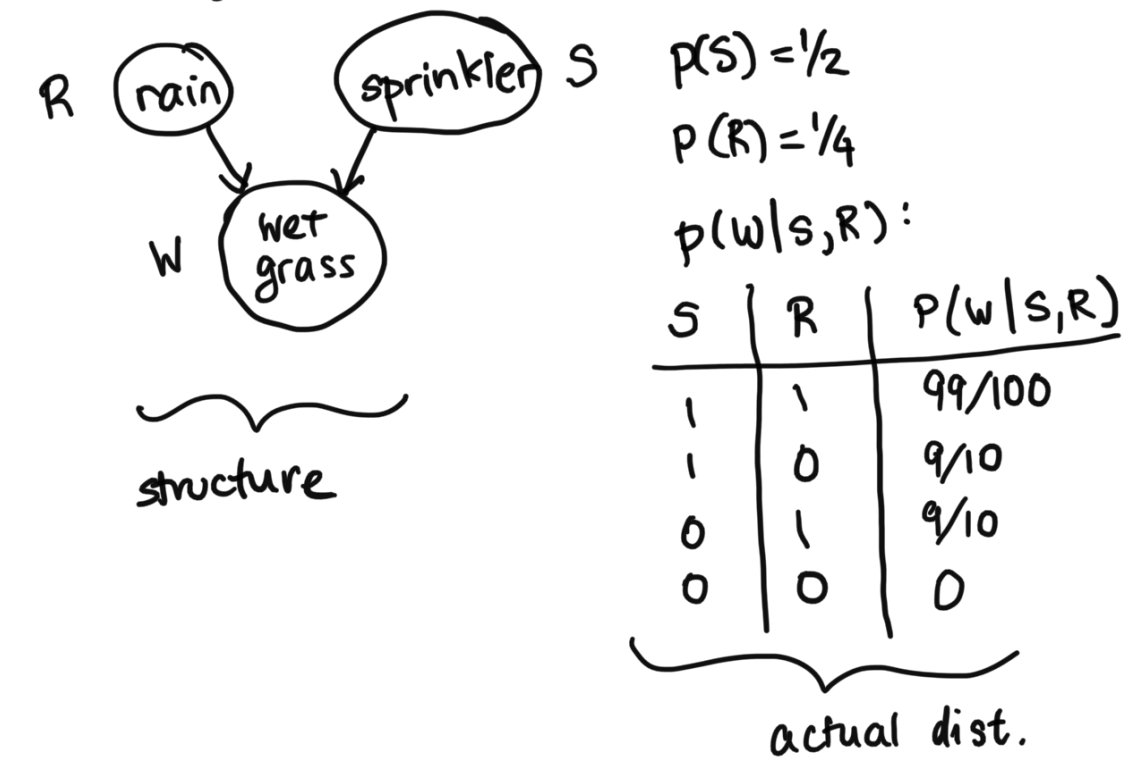

Let's try the following example, involving rain, a sprinkler, and wet grass:

Find the Probability It Rained Given Wet

Let's say we're looking to infer what the probability it rained given that we have observed that the grass is wet. $$p(R=1 | W=1) = \frac{p(R=1, W=1)}{p(W=1)}$$ $$p(R=1 | W=1) = \frac{p(R=1, W=1)}{p(R=1, W=1) + p(R=0, W=1)}$$ In order to do this, we actually have to break it down. This is exact same concept as what we wrote above in the section above, where we said we would have to sum over A, B, C. Here, because we don't know what happened with the sprinkler, we will have to sum over the different possibilities for the sprinkler. $$p(R=1 | W=1) = \frac{p(R=1, W=1, S=0) + p(R=1, W=1, S=1)}{p(R=1, W=1, S=0) + p(R=1, W=1, S=1) + p(R=0, W=1, S=0) + p(R=0, W=1, S=1)}$$ To make things concrete, we break down these values in detail: $$p(R=1, W=1, S=0) = p(R=1) p(S=1) p(W=1 | S=0, R=1) = (1/4)(1/2)(9/10)$$ $$p(R=1, W=1, S=1) = p(R=1) p(S=1) p(W=1 | S=1, R=1) = (1/4)(1/2)(99/100)$$ $$p(R=0, W=1, S=0) = p(R=0) p(S=1) p(W=1 | S=0, R=0) = (3/4)(1/2)(0)$$ $$p(R=0, W=1, S=1) = p(R=0) p(S=1) p(W=1 | S=1, R=0) = (3/4)(1/2)(9/10)$$ $$p(R=1 | W=1) = \frac{(1/4)(1/2)(9/10) + (1/4)(1/2)(99/100)}{(1/4)(1/2)(9/10) + (1/4)(1/2)(99/100) + (3/4)(1/2)(0) + (3/4)(1/2)(9/10)} = 21/51 = 0.41176$$ Recall that: $$p(R) = 0.25$$ This shows us how, if the grass is wet, the probability of rain has increased, from our prior of 0.25 to 0.41176 which makes sense intuitively. If the grass is wet, it's probably a bit more likely that it rained.

Find the Probability it Rained given Wet and Sprinkler On

Now, let's add a dimension of information in. What if besides the fact that the grass is wet, we also knew that the sprinkler was on. Intuitively, we should now get a lower probbility that it rained, because the sprinkler being on helps explain why the grass is wet. Let's make sure the math checks out: $$p(R=1 | W=1, S=1) = \frac{p(R=1, W=1, S=1)}{p(W=1, S=1)} = \frac{p(R=1, W=1, S=1)}{p(R=1, W=1, S=1) + p(R=0, W=1, S=1)}$$ $$p(R=1 | W=1, S=1) = \frac{(1/4)(1/2)(99/100)}{(1/4)(1/2)(99/100) + (3/4)(1/2)(9/10)} = 11/41 = 0.26829$$ This is indeed lower, and is now closeer back to the prior of 0.25. Again, this makes sense, because we also saw that the sprinklers were on (in addition to the grass being wet), which reduces the chances that it has rained, since the sprinkler has helped explain the grass has been wet. This is called the explaining away effect. It refers to one of the d separation rules we covered in last lecture.

Find the Probability it Rained given Wet and Sprinkler Off

For a sanity check, let's look at the other case, p(R=1 | W=1, S=0). This should actually be 1, because we had set p(W=0 | S=0, R=0) to be 0, basically saying that if it didn't rain and the sprinkler was off, there's no way the grass was wet. So if we know for a fact that it wasn't the sprinkler that cuased it to be wet (since it's off), that it must've rained with probability 1. Let's make sure the math checks out: $$p(R=1 | W=1, S=0) = \frac{p(R=1, W=1, S=0)}{p(W=1, S=0)} = \frac{p(R=1, W=1, S=0)}{p(R=1, W=1, S=0) + p(R=0, W=1, S=0)}$$ $$p(R=1 | W=1, S=0)= \frac{(1/4)(1/2)(9/10)}{(1/4)(1/2)(9/10) + (3/4)(1/2)(0)} = \frac{(1/4)(1/2)(9/10)}{(1/4)(1/2)(9/10)} = 1$$

Back to Original Setup: Choosing the Order of Elimination

From before, we had the following diagram.

As we do the sum over A, we notice that $p(C | A, B)$ is a cube of K by K by K numbers (since it has 2 children) and p(A) is a vector of size K. After the summation over A, we have a K by K quantity since we've summed out the A, but still have terms involving C and B, so we can rewrite this as a function g(C, B). We will have to deal with this at some point, but for now after summming out A we've turned this into a K by K quantity first.

As we do the sum over B, we notice that Vector B is of size K, and from before, g(c, b) is K by K. After the summation, we result in a new quantity g(c), which of just size K.

Finally, in the last sum, this gives the quantity of size K, the solution.

Note: this computation is now only $K^3$ (no longer $K^4$), which is way better. The reason is cause we only had to deal with the p(C|A, B) K by k by K cube term once. We compressed it into K by K right away, so the rest of the way we didn't have to deal with so many values. On the other hand, in the original method at the beginning of lecture, we had to deal with the cubed term over and over, leading to the $K^4$ computation.

Student Question: How do we sum up over A without any knowledge of B? This is a great question. When we sum over A, we are truly just eliminating A, so you're right, we don't know what B is. This is why in our resulting term g(c, b), it is still a function of B. Imagine we start with A B C, a cube of values. We're just summing over one dimension, the A, so we leave behind still a square which is B by C.

Important note: not all orders are necessarily better. We had our summations arranged in the order, $\sum_C \sum_B \sum_A$ which means we picked elminiating A, B, then C. If we had picked $\sum_A \sum_B \sum_C$ (also known as eliminating out C, then B, then A), we would still get $K^4$.

What does the min cost of inference depend on?

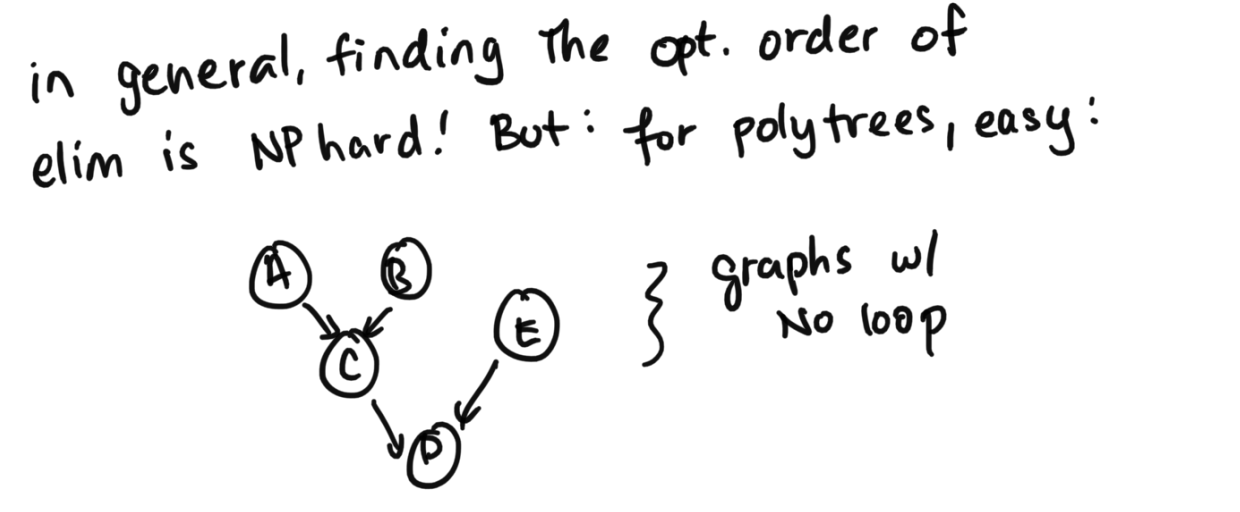

How do we determine the minimum cost of inference? This will depend on something called treewdith. One way to think about it is the maximum number of interacting variables. For us, our bottleneck was p(C|A, B), a triple dependency between variables. We definitely can't do anything better than that.In general, finding the optimal order of elminatin is NP hard. But if we have a specific structure, polytrees specifically, it's easy. A polytree is a directed acyclic graph whose underlying undirected graph is a tree (which means the undirected graph is both connected and acyclic).

How to get Optimal Order for Polytrees

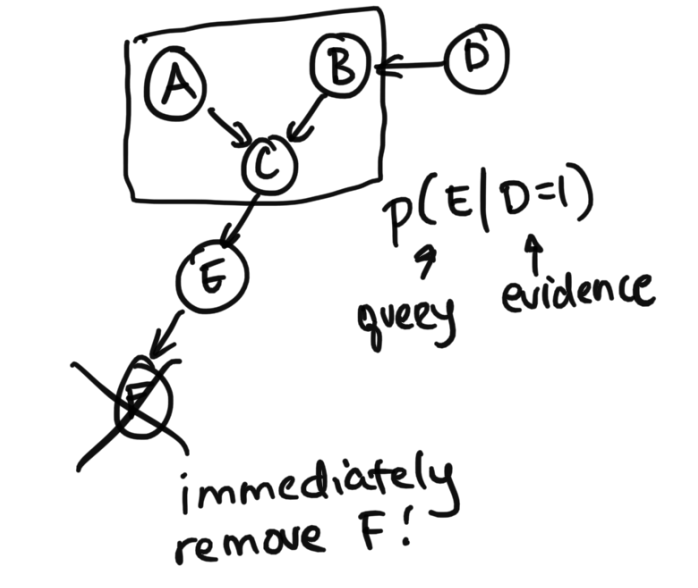

Step 1: Prune variables that are descenents of the queried or evidenced variablesFirst, we want to prune variables that are descendents of queries or evidence variables (also can be phrased as only keeping the ancestors of either).

Step 2: Find the leave and works backwards

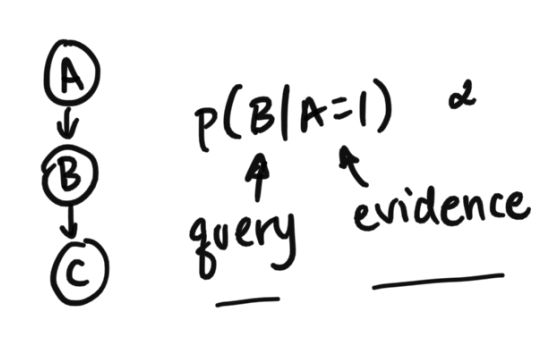

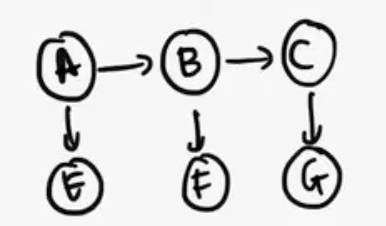

Next, what is important is finding the leaves (ignoring the directions of the errors) and working backwards to the query. We'll use this new diagram for an example of this one.

Preview to Next Lecture: Hidden Markov Models

Let's look at a specific form of structure, the Hidden Markov Model, which is something we will cover next class.

Let's say we have discrete values again, and we've observed our radar to tell us that E=1, F=1, and G=1. So let's say we're looking for p(C | E=1, F=1, G=1). $$p(C | E=1, F=1, G=1) = \sum_A \sum_B p(A) p(E=1|A) p(B|A) p(F=1|B) p(C|B) p(G=1|C)$$ How do we determine the proper order of elimination? Note that these are polytrees too. We also note, first of all there no descendents to be pruned away. Next, we see that for us to work from the leaves towards the query, so for us that means we want to eliminate A, then B (since A is furthest away from the query C). $$p(G=1|C) \sum_B p(F=1|B) p(C|B) \sum_A p(A) p(E=1|A) p(B|A)$$ As we sum out A, we notice that p(B|A) is K by K, and that after summing we will get a single vector K long, factor g(B).

As we sum out B, we know we will get another K size factor g(C).

These factors are often called "messages" (and you may see a message-passing algoirthm), which we will go into much more detail in the next class. But just to plant the seed first, the first factor g(B) is taking care of essentially the stuff in the past, because we know stuff about B with respect to the info from A and E. Then, the factor g(C), gives us the "message" about what's important from A, E, B and F. Again, more detail next class! The key idea is that in certain types of graphs, you can get some very specific patterns.

Note: What if we summmed it over a different way?

$$p(G=1|C) \sum_A p(A) p(E=1|A) \sum_B p(B|A) p(C|B) p(F=1|B)$$ As we sum out B, we see that all the terms inside, $p(B|A) p(C|B) p(F=1|B)$ is goign to be a K by K by K quantity (with, A, B, C), which will collapse to a factor g(A, C) after finishing the summing. Already, we notice that now we have something bigger than the other ordering.

As we sum out A, we will still have a g(C) vector.

Overall, we see that we have to store a K by K by K object and do the computation, so in terms of both computation and memory, the ordering from above is better.

Final Notes

There are really many algorithms for exact inference, but they're all the same ideas as what we covered today. It's good to know the other terminology out there so you can connect back to this.- Sum-product (this is equivalent to exact inference, it's also called this because our equaitons are sums of products)

- Forward-backward (this is equivalent to the specific sum product idea for hidden markov models)

- Junction-tree (this occurs more in the theory litereature, and refers to specific type of tree structures like polytrees)

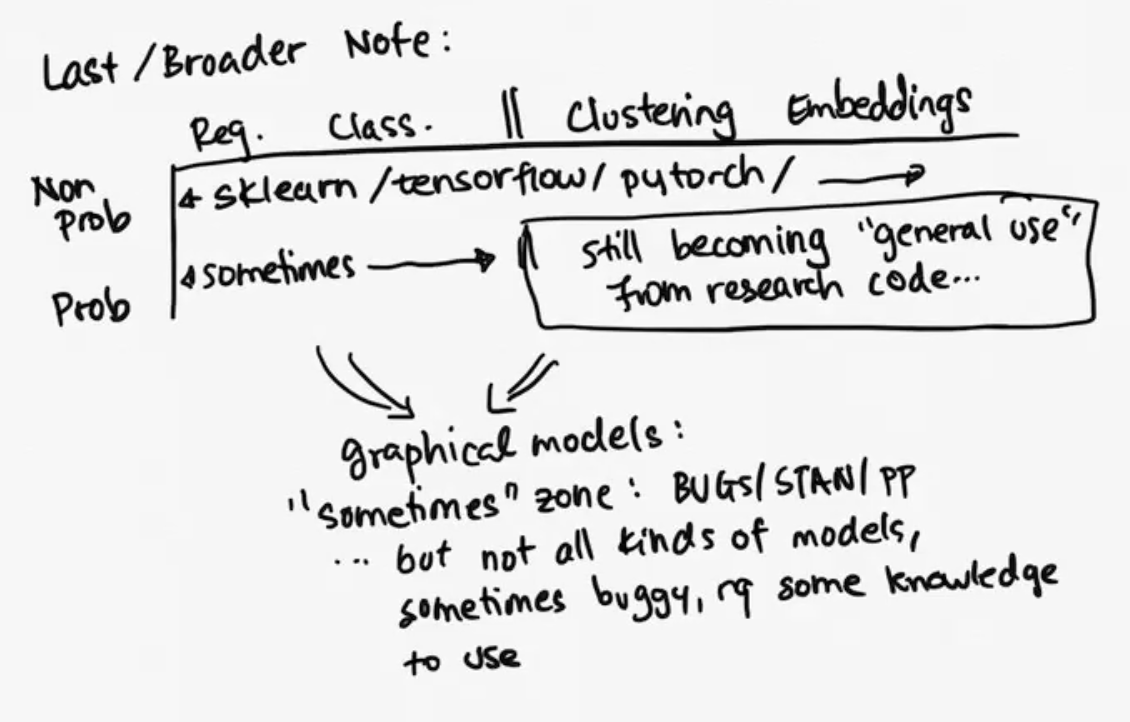

Final Broader Note